|

As dedicated systematic investors [1], we constantly strive to enhance our approach, ensuring it aligns optimally with our financial objectives. In recognition of the inherent unpredictability of short-term market movements, we resist the urge to time the market. Instead, we base any adjustments to our portfolio structure or investment strategy on solid evidence and evolving investment goals. Our unwavering commitment is to build a robust solution that empowers us to achieve our financial aspirations with confidence and prudence. The interest rates set by central banks have been rising in much of the world in recent times. One will have done well to avoid such headlines in the news. In the UK, the base rate set by the Bank of England was just 0.1% three years ago and now sits at 5%, at time of writing. This considerable increase – much of which happened in 2022 – led to historically low returns on bonds, as bonds fell in price in order to align with market yields. Despite rates not having been at such levels for some time, it is not unchartered territory. In fact, since 1975 rates have been above current levels more than half of the time [2]. For investors with medium to long-term liabilities (i.e., 5-10 years and beyond), the recent rate rises and corresponding price drops present substantial advantages. Due to the portfolio structure, the bonds, now offering higher yields, are expected to weather the price declines and subsequently generate higher returns. Additionally, this situation creates new opportunities for savers, making annuity rates and fixed-term instruments more viable in certain cases. Yet, when it concerns the anticipated returns on portfolios, the evidence remains unchanged. It is inherent in human nature to perceive a connection between risk and return. Therefore, it follows that if the expected return on cash has increased due to interest rate rises, the expected return on all other (riskier) asset classes must follow suit. Failure to do so would create an arbitrage opportunity, wherein investors could simply hold cash temporarily before reentering capital markets.

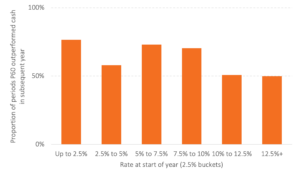

The reader will notice that there is no clear relationship between the level of cash rates and subsequent outcome of portfolio returns relative to cash. Over all 1-year periods in the sample, the portfolio outperformed locked up cash in two thirds of observations. The average excess return of the portfolio over cash in the 1-year periods was 4%. As we extend the holding period to 5- and 10-years the proportion of outperforming periods rises over 80%. Other practical implications are worth considering. Locking up cash reduces liquidity and may only be withdraw-able outside of the agreed period with a significant penalty. Also, savers with larger sums of cash need to be cognisant to spread cash across banking groups to remain under FSCS protection limits. Bank failures in the US this year offer a cautious reminder to savers not to naively ignore protection limits. Risk and return remain inextricably linked. The baseline has increased for all asset classes, a point we will be explaining to all clients at your regular meetings. Stick to the program. Yours, Clinton Askew [1] Systematic: ‘according to an agreed set of methods or organised plan’. Cambridge Dictionary [2] Bank of England |

We can look at historical figures to give an insight into whether there is a relationship between current rates on cash and subsequent portfolio returns. The figure below illustrates – at a given level of starting interest rate – the proportion of times in the subsequent year the portfolio outperformed this starting cash rate. In essence, this is seeking to answer the question: ‘if I lock up my cash today for the next twelve months, I am guaranteed x%, so why take on the additional risk of investing in a portfolio?’. Note that anything above 50% implies the portfolio performed better than locking cash up. The cash rate used is represented by the yield on a 1-year UK government bond, with an additional 1% added to reflect the higher rates that might be achieved through other entities offering fixed term cash accounts.

We can look at historical figures to give an insight into whether there is a relationship between current rates on cash and subsequent portfolio returns. The figure below illustrates – at a given level of starting interest rate – the proportion of times in the subsequent year the portfolio outperformed this starting cash rate. In essence, this is seeking to answer the question: ‘if I lock up my cash today for the next twelve months, I am guaranteed x%, so why take on the additional risk of investing in a portfolio?’. Note that anything above 50% implies the portfolio performed better than locking cash up. The cash rate used is represented by the yield on a 1-year UK government bond, with an additional 1% added to reflect the higher rates that might be achieved through other entities offering fixed term cash accounts.