We’re the masters of our own minds, except when we’re not. What about the times we buy things we don’t really want, or give to charities we had no intention of giving to? What causes us, when we’re primed to say ‘No’ to somehow end up saying ‘Yes’?

We’re the masters of our own minds, except when we’re not. What about the times we buy things we don’t really want, or give to charities we had no intention of giving to? What causes us, when we’re primed to say ‘No’ to somehow end up saying ‘Yes’?

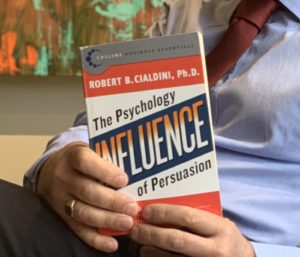

In Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Dr. Robert Cialdini, takes a long (and persuasive) look at the key ‘weapons of influence’ and explains how they affect us every day.

What makes it great, in a nutshell?

Cialdini’s book is based on thirty-five years of research but by distilling the science of persuasion into six key principles, with insightful examples, it makes for an easy and enlightening read. It uncovers unconscious behaviours and goes some way to explaining why we make the decisions we make, often to our own surprise.

Working through the book

We start with ‘Reciprocity’, the idea that people are more amenable to your wishes if you’ve given them something first. The American Disabled Veterans Organization found that by adding a small gift (personalised address labels) to a donation appeal the success rate went from 18% to 35%. It might seem mercenary, but give and take is a key factor in relationships, personal and business. When they break down, a lack of reciprocity is often a factor.

In ‘Commitment’ Cialdini’s explains psychologist Thomas Moriarty’s experiment in which a sunbather had their radio stolen. To begin with, only four passers-by intervened in 20 attempts, but when asked to “watch my things”, nineteen subjects took action. Commitment is powerful because inconsistency is seen as a negative trait, but it’s easily exploited. Look at how toy companies drum up business outside Christmas – by undersupplying shops with the latest craze, some parents are forced to buy alternatives. Later, when the adverts for the original toys run again, kids can hold their parents to promises already made.

We like to believe we’re immune to what everyone else thinks, but ‘Social proof’ is extremely powerful. Despite ‘hating’ canned laughter – telling us when to laugh – research shows it makes audiences laugh longer and more often. Doing what we see other people doing means we’re statistically less likely to make errors, but of course we can be swayed. The first few tips in a jar may not be there by accident, and in marketing, we’re forever hearing about the “fastest-growing” or “largest-selling” products.

Speaking of big sellers, there’s a Tupperware party hosted every 2.7 seconds. Tupperware doesn’t even bother to advertise, they just use the ‘Friendly thief principle’. Even if we know we’re expected to part with money, we’ll still do it where a social relationship is involved. Our host is a friend and neighbour and while they take a cut from every piece sold, we’re not being hoodwinked. We know we’ll be relieved of our money, but it’s much easier to continue down this route with a familiar face.

‘Authority’ explains an experiment in which people were asked to administer electrical shocks to ‘patients’ who answered questions incorrectly. As the shocks became stronger and the victims pleaded for release, the real subjects continued as directed. The ‘patients’ were actors and no real shocks were delivered, but the deference is what’s interesting. While many called for the experiment to stop, they still did as they were told by the perceived authority.

Finally, in ‘Scarcity’ we review the evergreen human state of wanting what we can’t have. As a way of coping with life there’s some sense here – better things tend to be harder to come by. But as consumers, we’re at risk, that’s why ‘limited edition’ is such a powerful concept and why shops have perpetual closing down sales. It’s also why, when we’re told we can’t have something – only to then be told we can have it if we commit right now – we’re more willing to part with our money.

So we’re being manipulated all the time?

Yes, and you could be forgiven for feeling cynical about the human condition once Cialdini shows us how malleable we are. But the book is a reference guide rather than an instruction manual. With the exception of reciprocity, which fits with just being a decent human being, this isn’t a toolkit of tricks, it’s a way to get wise to our own behaviours. It’s also perhaps a call to think twice about how we treat our customers. Doubtless, some of the meaner tricks here would work, but if we’re after long-term relationships, we’re looking to help, not hoodwink.